|

|

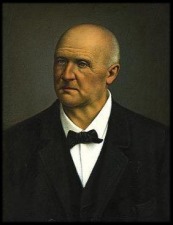

Anton Bruckner - An Introduction |  | |

His music has been championed by the greatest conductors of our time. Many of these conductors achieved their fame because of their interpretations of Bruckner's music. To many classical music lovers, Bruckner's music is the pinnacle of symphonic writing. Yet to others, his music is overblown and boring the product of an unsophisticated nineteenth century country bumpkin who needed the help of his students to put his scores into barely workable form.

It's hard to imagine that such widely divergent opinions could be pinned onto the same composer, but there are few cases in the history of western music where the life and work of a composer have been as manipulated and mischaracterized as that of the nineteenth century Austrian composer, Anton Bruckner. To this day, people continue to come up with conveniently simple motivations to explain this extraordinarily complex and gifted organist and composer.

Bruckner was born in Ansfelden, a small rural town in upper Austria (near Linz) in 1824. In the early nineteenth century, life in this region was very different from that of Austria's political and cultural capital of Vienna. Bruckner's upbringing and early life experiences and his devout Catholicism did little to prepare him for Vienna's overly stylized and often shallow cultural climate. His musical abilities soon led him to Vienna but his manner and outward appearance made it difficult for him to gain the recognition he deserved. Bruckner's selfless dedication to his art was something that many of his Viennese contemporaries had difficulty grasping. For them, music was as much about politics as it was about art. For Bruckner, his world revolved around his faith and music.

One famous example illustrates his situation perfectly. Early in his career, Bruckner openly recognized the tremendous musical talents of Richard Wagner and was a life-long champion of his music. But by liking Wagner's music, Bruckner was now at odds with many of Vienna's musical elite who were feverishly championing the music of Brahms while opposing anything to do with Wagner. Today, such a debate would be viewed as ridiculous, but in Vienna, this debate raged on for years and Bruckner unwittingly got caught in the middle of it. As a result, he became the target of some very strong and highly placed criticism. His compositions were dismissed by some even before they were heard. Bad reviews were guaranteed, yet even the casual listener can hear that Bruckner's compositions are uniquely his own and bear very little resemblance to the music of Wagner. It was a politically motivated agenda which had little to do with the true worth of the music being discussed, but the proper recognition of Bruckner as a composer was clearly a casualty.

Many biographers attempt to explain Bruckner's difficulties in Vienna by characterizing the composer as a simple man thrown into a complex society and how his music was often doctored and touched up by well-meaning but ill-advised and over zealous disciples. But Bruckner was no simple man. He may have lacked some of the cultural cultivations of the Viennese, but one could not write symphonies of this magnitude without having a mind that could grasp extremely complex concepts. Nevertheless, biographers would characterize Bruckner as a simple-mannered peasant in "dusty clothes" who could somehow compose incredibly complex symphonies. Further, with the exception of the Ninth Symphony, which was left unfinished at the time of his death in Vienna in 1896, it is now clear that Bruckner had a hand in overseeing his publications and openly pushed back on many of his disciples' suggestions. He was not as easily swayed in his beliefs as some would lead us to think. He also was forward thinking enough to entrust his manuscripts to the Austrian National Library. Bruckner did what he could to protect his works for posterity. He did as much as any mortal man could do and, leaving no heirs, he rested his case solely on the contents of his manuscripts.

But it was after Bruckner's death that some very strange things began to happen. First, his disciples moved forward with the publication of his unfinished Ninth Symphony and here they placed their "retouchings" and re-orchestrations at a time when the composer could no longer approve or disapprove of them.

Then, in the 1930's, Bruckner's music was embraced by the National Socialist (Nazi) Party in Germany. Adolf Hitler, himself born in upper Austria, felt a connection to the composer and saw a use for his symphonies as a musical symbol of the power and purity that Hitler was to promote in such an evil and sinister way. Hitler had his propaganda minister, Joseph Goebels incorporate Bruckner's music into his very effective propaganda machine. Bruckner's music represented a cultural purity, and now the suggestions by his students and disciples were held up as examples of bourgeois meddling which needed to be purified. While the resulting "original editions" that were produced at this time, under the direction of Robert Haas, had some value in cleaning up textural matters and eliminating the ersatz and heavy doctored edition of the Ninth Symphony, the characterization of Bruckner as an unwitting subject of editorial meddling did much to rekindle a false impression of the composer. These "original editions" and the rational behind them lasted much longer than did the propaganda machine that created them. Today, some of those "doctored" scores are being re-evaluated and are being represented as reflecting Bruckner's true intentions. Further, while some of Haas' original editions have stood the test of time and further scholarly review, some have been questioned due to Haas's tendency of amalgamating different versions of Bruckner's symphonies into one performing edition something the composer had never approved of during his lifetime.

Like so many geniuses who have enriched our lives from Beethoven and Mozart to Van Gogh and others - Bruckner was extraordinarily gifted in some areas and wanting in others. He was awkward around women and cared little for how he dressed (again, he was not a good fit for Vienna). He preoccupied himself by counting everything, windows, trees, cobblestones - everything. It was his way to find order in complex patterns. He studied music theory for years before producing his earliest orchestral works. This discipline undoubtedly helped him as he built the structural framework of his enormous sound canvases and with each symphony; Bruckner expanded the concept of the symphonic form in ways that have never been witnessed before or since.

The remarkable aspect of Bruckner's music is that he was able to do so much without breaking the structural design of the symphonic form. As early as his Second Symphony, Bruckner was writing adagios with an incredible melodic flow that could sustain them without pause for up to one half hour. When listening to a Bruckner symphony, one encounters some of the most complex symphonic writing ever created. As scholars study Bruckner's scores they continue to revel in the complexity of Bruckner's creative logic. But one does not need to understand the underlying complexities of Bruckner's music to enjoy it. No doubt, the structure holds these works together, but there is always the pleasure of simply sitting back and letting the sonorities of Bruckner's music wash over you.

There is a reason why Bruckner's music is so often performed in cathedrals. Part of it has to do with the composer's religious beliefs and his experiences performing and improvising on church organs throughout Europe. Bruckner was openly recognized as one of the greatest organists of his day. But it is the sonorities of Bruckner's symphonies and how they can fill such large spaces that have so many conductors and orchestras looking for special places to perform these masterpieces of structure and sound.

When dealing with Bruckner's symphonies, one cannot avoid another of Bruckner's little foibles and one that has added to the confusion around his compositions. As a composer, Bruckner could never leave well enough alone. Many of his symphonies were the subject of numerous revisions. Sometimes, these revisions had to do with preparation for performance or publication, but some were merely the product of an active musical mind who liked to come up with different solutions to a structural and melodic puzzle. Compounding this issue is the fact that Bruckner not only left us with different versions, but over the years editors have given us many different editions of these different versions in what can now be described as a frightening number of available scores and performing editions. It is enough to confuse the most devoted of Bruckner enthusiasts. It has also, unfortunately, given license to conductors and musical scholars to make their own adjustments to Bruckner's scores.

The discography on this website is an attempt to help sort out the different recorded performances and to list them under their proper editions.

John F. Berky

March 22, 2006

|

|

|

ABruckner.com

ABruckner.com